In a first-of-its-kind case, the Justice Department is prosecuting an Internet troll, using a Reconstruction-era law to claim that a series of social media memes were “an attempt to deprive individuals of their constitutional right to vote.” “

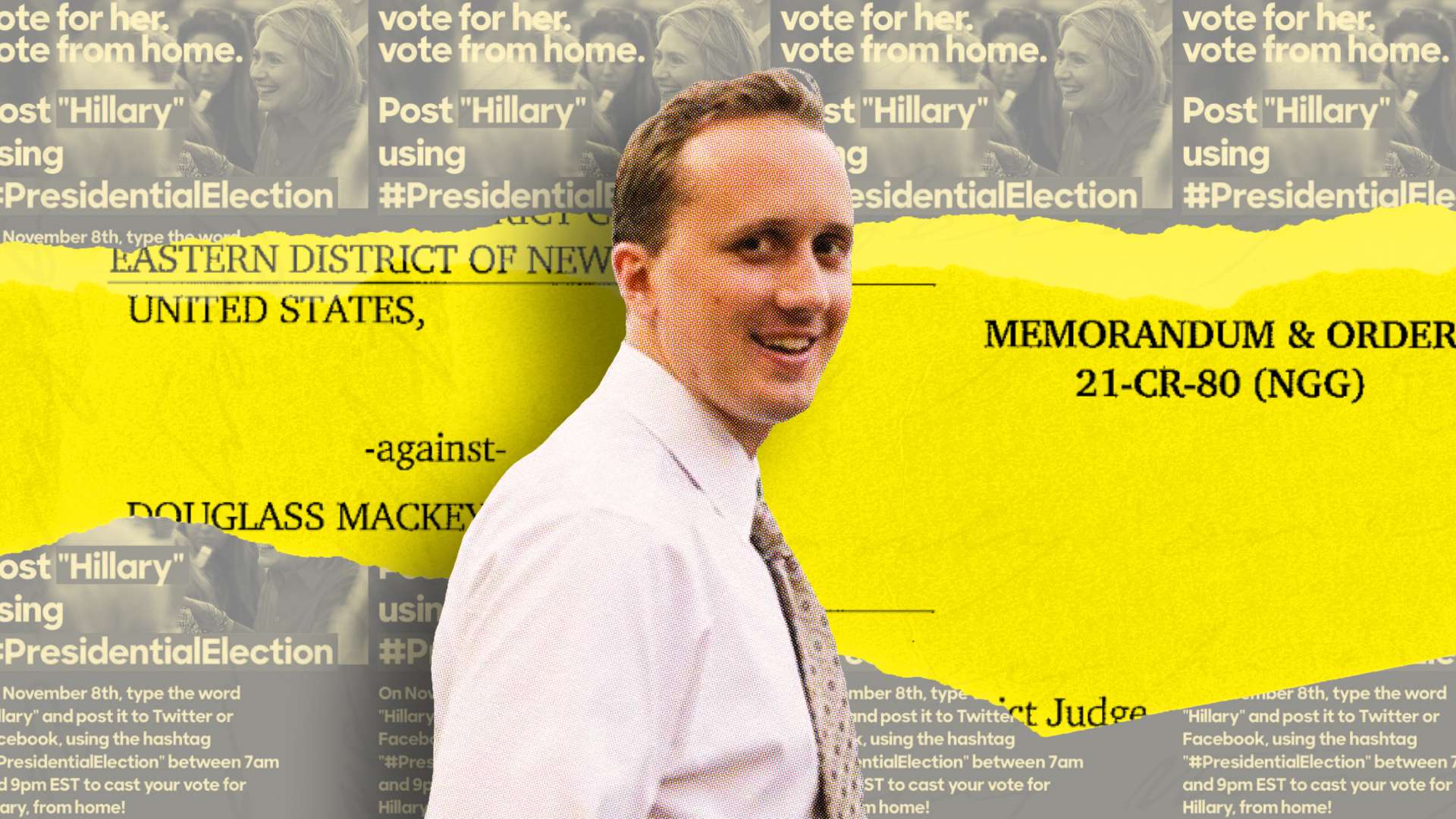

During the 2016 election season, Douglas Mackey was a far-right Twitter user named “Ricky Vaughan”. Mackey often posts pro-Trump memes and comments to his 58,000 followers. An MIT Media Lab analysis claimed he had more influence in the 2016 election than NBC News.

At one point he posted a series of images intended to trick Hillary Clinton supporters into thinking they could vote via text. “Skip the line. Vote from home,” one of the images read over a Clinton-branded backdrop. Text ‘Hillary’ to 59925. At least 4,900 people texted the number before Election Day, according to a Justice Department press release.

Federal officials say it was a deliberate attempt to violate voters’ constitutional rights. On January 27, 2021, they charged McKee with conspiracy “to injure, oppress, threaten, and intimidate one or more persons in the free exercise and enjoyment of a right and privilege protected by the Constitution and laws of the United States: to vote.” rights.” Their case rested on an 1870 law designed to prevent violent white supremacist mobs from preventing black citizens from voting. The Justice Department believes this is the first time an American has faced criminal charges for misinformation on Twitter.

McKee tried to have the case dismissed in district court last month, arguing that his tweets were satirical and First Amendment-protected. His motion to dismiss was denied. Judge Nicholas G. Garoufis wrote, “This case is about conspiracy and injury, not speech….As applied to the indictment, the statute is used to prosecute a conspiracy to defraud people from voting — conduct effective through speech — not to effectuate that goal. A special offense for pronunciation.”

Aaron Terr, an attorney with the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, disagrees. “The First Amendment presumptively protects all speech unless it falls into a specific, narrowly defined category established by the Supreme Court. And the First Amendment does not provide a general exemption for false speech,” he says. “There are certain types of false speech that are exempt from the First Amendment, such as defamation or fraud,” but McKee’s speech clearly does not fall into either category.

Eugene Volokh, a professor at the UCLA School of Law, recently offered a suggestion tablets The article states that “narrow and narrowly defined statutes that prohibit lying about the voting process are probably constitutional” but also notes that “there is no such clear and narrow federal statute” in Mackey’s case. He added that when similar issues come up in court, judges are generally “quite skeptical of general prohibitions on election perjury.”

If McKee is convicted, it would pave the way for direct government regulation of a wide range of speech labeled as election “distractions.” The consequences could be far-reaching – perhaps a range of anti-suffrage speech could be the subject of criminal prosecution

“I suppose you could reasonably ask what would happen [the Justice Department’s interpretation of the law] Applies to something like discouraging people from voting? What if a large number of citizens sit on election day? Is it damaging the election process? Is it harming democracy?…Giving the government that kind of authority is dangerous.”