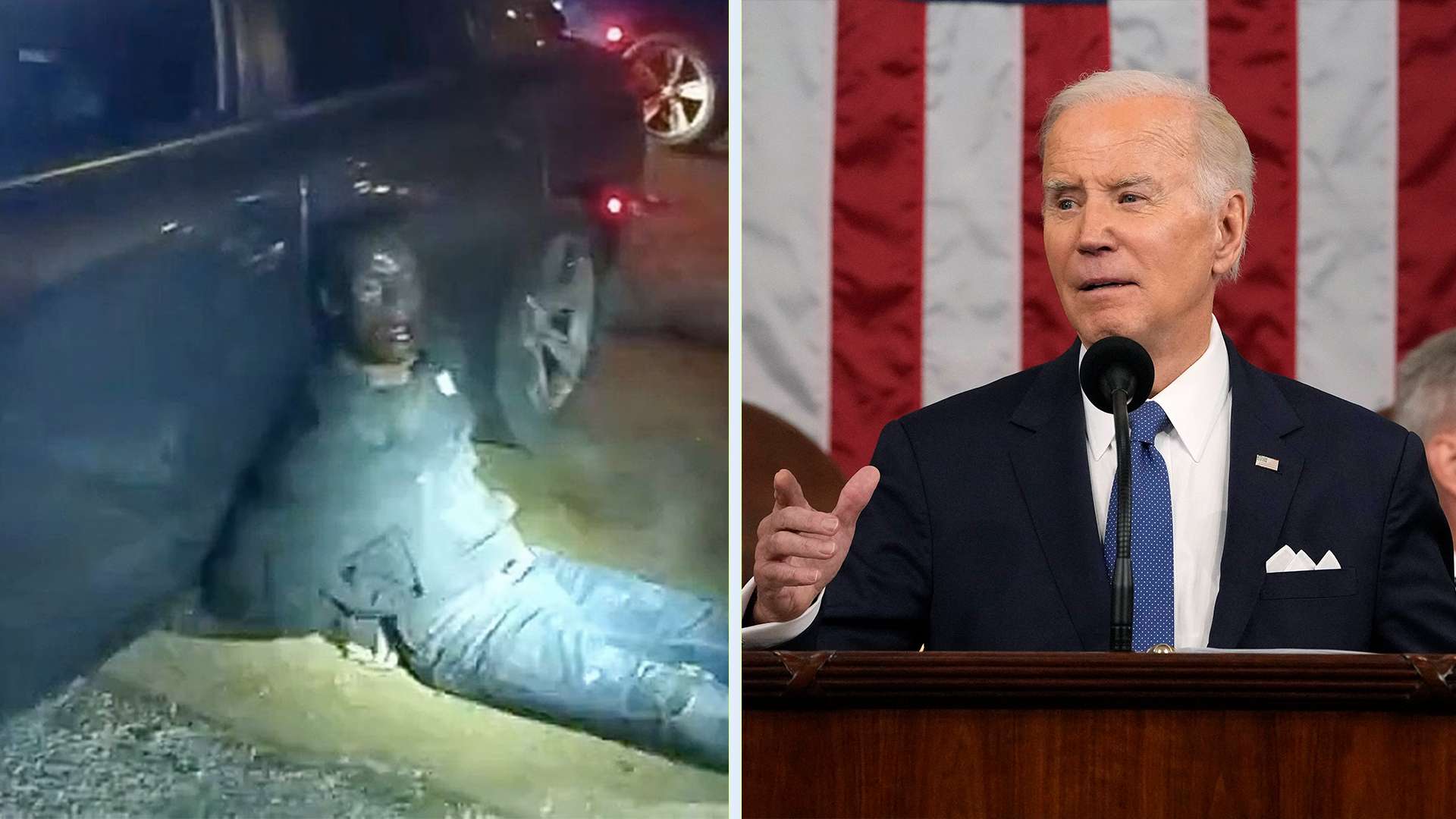

In his State of the Union address last night, President Joe Biden introduced the family of Tyre Nichols, who was killed by Memphis Police Department (MPD) officers during a traffic stop in early January. The footage, released weeks later, was brutal and almost universally condemned, reviving a simmering debate about how to provide some justice to victims of state violence after their rights have been violated by the government.

“When police officers or departments violate the public’s trust,” Biden said, “we must hold them accountable.”

Absent from his speech was a suggestion of how to do this or how to ensure some form of recourse for victims of state malfeasance.

This is not the case because such a path does not exist. But the issue has become politically charged, even though it needn’t polarize people along partisan lines.

In the summer of 2020, the federal government appears poised to propose some form of reform to qualified immunity, the legal doctrine that protects local and state government actors—not just the police—from facing federal civil lawsuits when they violate someone’s constitutional rights. since the manner in which they violated the Constitution was not “clearly established” in prior case law. It explains, for example, why two policemen allegedly stole $225,000 while executing a search warrant could not be sued for the law: although we would expect most people to know it was wrong, there is no court precedent. which states that theft under such circumstances is a constitutional violation.

It is an absolute standard that would defy parody in that it prevents victims of government abuse from seeking compensation in response to government misconduct. For example, in the case of Tyre Nichols, it is quite plausible that the officers who killed him could be convicted of murder and still Get qualified immunity – a testament to how inconsistent and unforgiving this doctrine can be.

This is not a hypothetical. Consider the case of Bau Tran, a former police officer in Arlington, Texas, who was charged with criminally negligent homicide in 2019 after he shot and killed a man while trying to flee a traffic stop. (The case is still pending.) Tran was granted qualified immunity by a federal court ruling that it “has not so clearly established that per A reasonable officer” would have known that his specific conduct was unconstitutional. The deceased O’Shea Terry, first obeying the traffic stop and then attempting to drive away, told Tran to jump on the side of the car and ultimately fired five shots. The car. Possibly one of Tran’s peers was Jury Terry. would have denied the family compensation. But we’ll never know, because the family would be legally barred from even asking.

Accountability through the criminal courts is part of the equation. But prosecutors are often hesitant to bring such charges, and a charge is not the same thing as a conviction. Should the officer who accidentally shot a 10-year-old boy while targeting a non-threatening pet dog face prison? Reasonable people might disagree, although it is arguably less plausible that the mother of that child will not receive compensation for the medical care her son needs because of the government’s negligence and abuse. Yet that was the reality for Amy Corbitt, who couldn’t ask a jury to consider her civil case. The officer who shot her child received qualified immunity (and was not charged with a crime).

Those skeptical of qualified immunity reform generally cite an uneasiness about bankruptcy officers. They may note that cities indemnify their employees against such claims, meaning the government settles any. This is certainly an imperfect solution to holding individual bad actors accountable, but it does provide an outlet for victims of state abuses to achieve some semblance of reparations. Make any settlements out of the police pension fund and you’ve created a big incentive for the department to extort its consistently problematic actors.

Biden’s reluctance to promote the doctrine by name on Tuesday is an indicator of how vulnerable the issue has become after years of over-characterizing the criminal justice debate. In the case of qualified immunity, however, an inverse relationship exists between debate and relaxation across ideological lines. The doctrine drew the ire of Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas and Sonia Sotomayor, while the two disagreed. People on the left may bemoan barriers to police abuse. Those on the right can zero in on the doctrine’s tendency to green-light big-government malpractice, as well as its genesis as a result of judicial activism at the highest levels. Instead, we have a status quo where government protects itself at the expense of the people it serves.